Shaun Scott’s Heartbreak City: Seattle Sports and the Unmet Promise of Urban Progress unfolds like a baseball game. First through its structure: divided chronologically, recounting a people’s history of Seattle into nine innings—and some extra bits—corresponding to key eras between the start of white settlement and today. Then through a vibrant array of characters shaping how history unfolds: divulging their shared hopes, committing errors, moving through losses, rallying.

Heartbreak City is as much about casting a light on keystone, bygone sports dynasties—from the superspreading Metropolitans hockey franchise to the stunning Seattle Owls—as it is about questioning Seattle’s teams, champions, and projects the city rallies behind. That the city doesn’t rebuke its “Loserville, USA” moniker by proudly citing the Seattle Storm’s impressive record, or OL Reign’s winning proclivities, or Floyd Patterson’s historic boxing match against Pete Rademacher (who? read the book!) speaks volumes. Misguided affinities shape, and are further re-entrenched by, the city’s collective identity and its political roadmap. Leading to whopping investments in professional sports infrastructure but not housing or community centers or other elemental needs; and making only some worthy of citywide celebration for their victories after defeat.

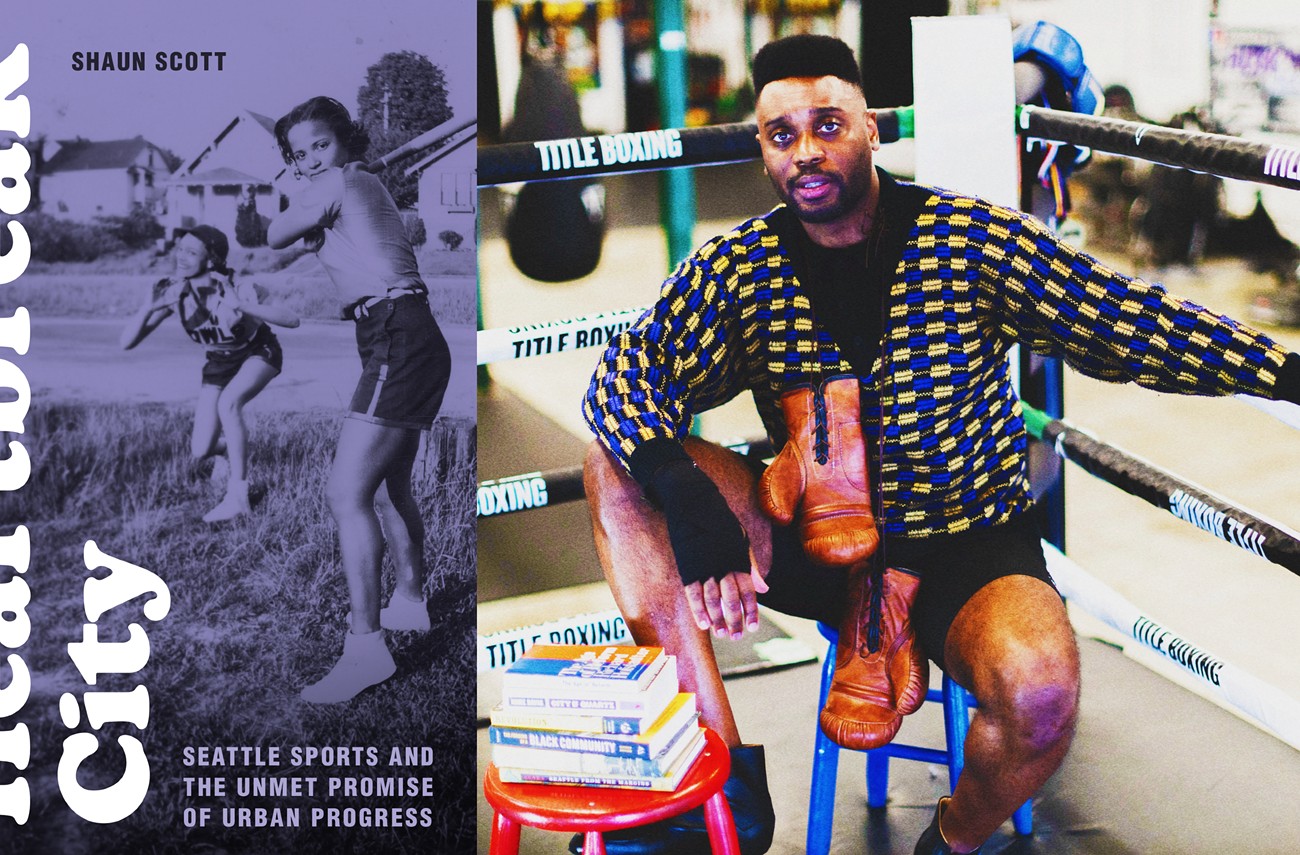

In an interview with The Stranger, Scott, a political organizer and one-time City Council candidate (and occasional Stranger contributor), describes the loss driving his work, dives into the book’s non-sports lessons, and analyzes the political economy of stadium projects.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

I know you wrote the book in part because you were commissioned by UW Press, but I’m interested in why sports is your lens. And I’m wondering to what extent that has to do with the multi-constituent political vocality you wish to espouse.

The project itself didn't really materialize until the stillness and the quietness of quarantine set in in spring 2020. The sports calendar was put on hold in ways that I had not seen in my lifetime; 9/11 was the only other time that I could really remember reams and reams of games being canceled, entire portions of the sports calendar being put on hold and delayed.

For many people, the impact of quarantine was felt as not being able to go to their favorite coffee shop or not being able to go to their favorite movie theater. For me, I think the civic connection that is felt through the games that we play and the games that we watch was a real felt loss. So the book, in a lot of ways, started from a place of mourning for that lost connection or for that deadened connection.

Putting together a people’s history of Seattle and trying to tell the truth about the city and aspects of its politics that played out: I don't think that it's possible to really do something like that from a calculated perspective. In other words, I found after being very, very busy nonstop campaigning for three or four years, I actually really embraced the lack of political calculation and “strategery”—as George W. Bush [played by Will Farrell on Saturday Night Live] put it years ago—that the writing process presented.

No matter where you are, as a writer, there you are. It's impossible to divorce a lot of the memories you might have about how certain things have played out politically and, from that, attempt to tell the truth about the city's history. I think any connection that might arise between the diagnosis of the city's history—which goes all the way back to settlement and comes all the way up to the recent era—and politics just comes about as a matter of trying to find the truth.

Totally. I mean, the Genesis or Original Sin of settler history starts off with the Denny party’s arrival while Indigenous people are playing sports. That’s something that transpired rather than a forced connection [between sports and history]. Or there’s the way history rhymes with George W. Bush throwing the first pitch at the World Series, just as he did in 2001, with geopolitical conditions being in many ways the same as they were 22 years ago. A throughline you don’t need to force as much as it is just being. Regardless—presumably—quite a bit of this history wasn’t knowledge that you already had; what sort of information did you stumble upon versus actively seek out to create this sports-oriented lens for a people's history of Seattle?

Well, the research process comprised the majority of the labor of putting this book together. Very early on, I decided that I wanted to try to tell a moralistic story rather than a periodized one—focusing on the entire city's history, rather than on a particular era—because the throughlines that you mentioned come out, and are that much more apparent, when you see exactly how far back they go.

Now, of course, with that vision comes a considerable research burden, because now you're attempting to do a lot more uncovering versus a lot of interpreting. I would venture to say that somewhere north of 70% of the content of the book was information I did not know about before the research process. To give you an idea of what that process looked like: I want to say seven or eight versions or drafts of this book were generated over the course of two and a half years.

The majority of the energy was spent on the primary source data. And somewhere in the negotiation between that primary source material, which was the richest part of the research process, and that secondary-source big picture perspective is where you get the narrative that comes through in the book.

And you juggle the two [source types] really, really gracefully. This book came out of an era of quarantine and loss of connection, and your archival research further uncovers reams of missed opportunities: whether it's Forward Thrust, a floating stadium, genuinely equitable municipal policies, or the sustained existence of the Seattle Owls. I'm curious how you moved through that dual loss over the course of writing the book.

It's a question of how a city deals with defeat, how populations deal with disappointment, and how individuals can remain resilient in the face of (at times) overwhelming odds. This idea came up over and over again by looking at the individual characters that were in the book. The hope was to try to put something together that read in some ways as much like a novel as it did a history book, in the sense that you have characters that lead really interesting lives that overlap eras, maturing at the same time and in the same ways as the city is maturing.

It's Lenny Wilkins receiving hate mail when he's instituted as the Sonics’ player-coach in the latter 1960s. It's Helene Madison, the swimmer during the Great Depression who falls apart after she puts Seattle on the map and becomes the city's first sports superstar. It's the story of Robin Threatt, the guard who played briefly for the Seattle Storm as a woman in her early 30s, who had given up on the idea of being a professional basketball player, sees that the WNBA is formed, moves to Seattle sight unseen, tries out for the team and beats out women 10, 11 years her junior.

I think the recovery aspect of these stories are way more important to me than the disappointment aspect. I think the initial disappointment in so many athletes’ athletic careers and in so many political pursuits is almost an inevitability. But the real question is: What can the city do to recover? In a sense, recovering these stories from the archives of history, and from history books, and from microfilm was the part of this whole process that was the most inspiring to me.

That's where the reconciliation comes in: in realizing that disappointment is inevitable, and defeat is inevitable, but what is not inevitable is the recovery. That's the decision that we have to make. In the same way that I think every athlete had to make that decision for themselves about whether or not they were going to let initial defeat define what they were about or whether or not they were going to push forward. The Sonics won the title in 1979, the very year after losing to the same team that they ended up beating in '79 in the finals—and with Lenny Wilkins as the head coach, a guy who had been receiving hate mail from the city's fans only a decade prior. As you read stories like that you can’t help but understand that the real value in these stories is in their value as a model for resilience and for recovery.

You mentioned in the first few pages of the book how sports shape the city hand in hand with frontierist practices—like being a lumberjack or having a predominantly male population. How much do you see that ethos continuing today? I mean you talk about “frontierist rambunctiousness” at one point when talking about the Seahawks in your book. So I'm wondering how much you still see that ethos impacting the forms of leisure and self-identity that define the city today.

I think there is an inherent settler mythology that is inseparable from athletics and the idea of a population venturing out West and building, in their minds, a city from thin air. Politically, what you see in the city at present is a kind of libertarian progressivism and a fear of bigness, be it big government, or big development, or big huge corporations. But there's a perennial identity crisis that I think exists in the city—where at the same time that the city’s pro-business boosters want to be recognized as belonging to a very metropolitan city, many of the people here have reason to actually fear what taking those steps into the future might mean.

So Seattle as a city always feels like it’s almost arm-wrestling with itself about how to move forward, or whether to move forward. All of that is really not separable from our geographical position historically, and from the kinds of fights that we've had over whether to build transit, whether to build housing—if so, where to put it—whether or not a huge stadium is the thing that finally can make the city say it arrived, or whether that actually is just a waste of money. These are civic debates that cut to the identity of the city, ones I tried to unfold layer after layer and look at how they played out over generations.

I think it’s interesting that you are, in a lot of ways, very pro-stadium. Often stadiums are seen as this pork-barrel, billionaire-pocket-lining form of civic infrastructure. You add nuance by describing how certain stadiums are funded. Regardless, something that can congregate 50,000 people in one venue in the name of a collective identity or a collective pastime is the locus of so much debate.

The section that deals with the implosion of the Kingdome and what the Kingdome represented gets at the heart of this. I mean, in deciding to detonate the Kingdome and build the facility that eventually became Lumen Field, I think I do describe that as “pissing away close to a billion dollars,” so it's not a completely pro-sports-boosters apologist take.

No, no, no, of course not.

I would say that the celebration comes from the fact that sports facilities are some of the most visible examples we have of the collective mobilization of huge gobs of public resources, with a layer of emotional excitement added to it. It’s not just public and civic investment as a form of eating your vegetables; this is something that people really happily embrace.

If there's a criticism, it comes from the fact that similar forms of public mobilization, which probably would cost less money and require less effort, are not made. We see huge stadiums go up, constructed with organized labor in a matter of four or five years, in the same city where we have people sleeping outside. So you wonder, where is that engineering might? Where's the civic vision? Where's the enthusiasm for marshaling those resources when it's a question of the stakes being much higher? So therein lies the conflict.

By framing the stadiums as strange deviations from the capitalist ideal—when you consider not just the gobs of public funds it took to build them, but the fact that the workers in the stadiums, from the concession stand workers to the players, are majority organized laborers—sports come with a specter of socialism that I think a lot of people would not recognize at first glance. But when you break it down, you see a lot more collectivism in our sports than you do the individualistic capitalist ideal.

Shaun Scott discusses his book, Heartbreak City, with Jesse Hagopian at Town Hall Wednesday, November 29 at 7:30 pm.